A small,

grey-haired gentleman climbed the few steps and surveyed his auditorium. Rows

of polished oak benches were neatly lined up before him and the stove towards

the rear of the left-hand side was stoked, its heat beginning to fill the room

and flow into the worn, wooden floor taking away the evening's chill.

From the inside pocket of his jacket

he took a small book with a burgundy cover, and placed it upon the lectern. The

honeyed smell of bees' wax that had been used to polish the pulpit's wooden

frame rested in the air. Sitting down on a red velvet cushion he watched as seats began to fill until there was not a spare place to be had; any latecomers

would have to stand.

The clock on the wall struck seven

and candles spluttered and flickered as they balanced along the dado rail, which ran along

the top of the polished wainscot around the small chapel. He stood, cleared his

throat and opened his book. Just as many Christmas Eve's before, he addressed

the gathering.

"Marley was dead, to begin

with. There is no doubt whatever about that… Old Marley was as dead as a

door-nail."

He skipped the next paragraph and

continued: "Scrooge knew he was dead? Of course he did. How could it be

otherwise?"

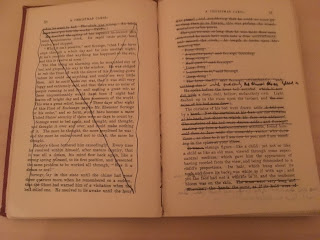

Mr J. T. Hardy turned the pages,

skipping some paragraphs and adding in some of his own words.

Much of Stave One, Marley's Ghost, was crossed out in the

book as was Stave Two, The First of the

Three Spirits and the beginning of Stave Three, The Second of the Three Spirits. He turned to page fifty and read,

not the words of Dickens, but his own.

"Scrooge awoke in his own

bedroom. There was no doubt about that. But in his own adjoining sitting room,

into where he shuffled in his slippers, attracted by a clear light, there had

undergone a surprising transformation."

Page fifty-three gave a

clear description of the second spirit, The Ghost of Christmas Present, in his

green robe with white fur, but Mr Hardy chose not to give his audience the easy

way to see this apparition, instead allowing them to use their imaginations to

create their very own. This was their conscience that would speak to each of

them independently and discretely.

The pages of Stave Four, The Last of the Spirits was untouched

and he read every word of Dickens's final twenty-four pages. When he concluded with:

"It was always said of him [Scrooge] that he knew how to keep Christmas

well. May that be truly said of us, and all of us! And so, as Tiny Tim

observed, God bless us, Every One!" the villagers rose to

their feet and applauded the small, grey-haired man. Many had heard him tell

the tale so many times before, others had heard it for the first time, and

would hear it again, next Christmas Eve, until he could tell it no more.

*

A Christmas Carol was written in October 1843 when Charles Dickens

was thirty-one, and published just before Christmas that year. Its message of

love and trust was carried to fifteen thousand homes in its first year. It was

also pirated almost immediately, but Dickens remedied that misdemeanour in a

court of law.

My mother was one of the villagers

(Seagrave in Leicestershire) who attended the reading of the story by Mr J. T. Hardy, which he did from the village chapel's pulpit each Christmas Eve for many years.

She often told me of these annual readings and his widow gave the book he

read from, with his annotations, to me when I was a child.

I hope he is still entertaining Mum,

and all the other villagers who loved his storytelling, in the next world. And

you never know, Dickens himself might be joining in too.

God bless us, Every One!